Pt. 1 of the Wildfire Series

April 14th, 2025

The Elephant Butte Fire

A prop airtanker drops Phos-Chek retardant just north of the butte.

On July 13th, 2020, Evergreen, CO experienced a dramatic fire in the center of the community. With hundreds of homes around and in the fire’s direct path, surrounding areas were quickly evacuated by JCSO (Jefferson County Sheriff’s Office), including south of Elk Meadow and around Alderfer/3 Sisters Park. The fire burned for 2 days.

Elephant Butte is a central prominence situated in unincorporated Evergreen, CO. just north of Alderfer Park, topped by rock formations and trees and loosely surrounded near the base by homes with large lots. Likely due in part to its proximity to the central population, considerable resources were allocated to deal with the inferno. The butte and land around it are managed by Denver Mountain Parks, with adjacent area managed by Jeffco Open Space.

Multiple departments fought the fire together, including the 20-person Tatanka (SD) and Pike (CO) Interagency Hotshot crews. Overall, there are 113 Hotshot crews in the U.S., five in Colorado.

Rocky Mountain Area Coordination Center (RMACC) dispatched several aircraft. Possible reasons for the high number of aircraft involved was the difficulty ground crews had reaching the advancing flames due to the steep terrain. That, and the good fortune the resources were readily available and on alert in a time of long-term drought and highly destructive wildfires in the West.

Of the three airtankers, one was a jet.

Two Erickson S-64 Helitankers and two small prop planes were used to make more precise drops at the edges of the advancing fire.

The Elephant Butte Fire preceded the infamous Marshall Fire by a year and a half. A common denominator between them - both began in a wildland–urban interface (WUI) - one in adjacent grassland and the other next to a forest-embedded neighborhood. The cause of the fire is undetermined, but lightning/nature were ruled out. In the end about 40 to 50 acres of woodland were destroyed, but no lives or homes were lost.

The fire occurred during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. For some people this crisis added to a prevailing sense of dread, but once it was clear the threat had passed, the relief we shared felt joyful. The nightly 8pm howling in my neighborhood, as a homage to emergency responders worldwide, took on greater meaning in the aftermath.

In the afternoon/early evening of the 14th a rainstorm gave a timely assist.

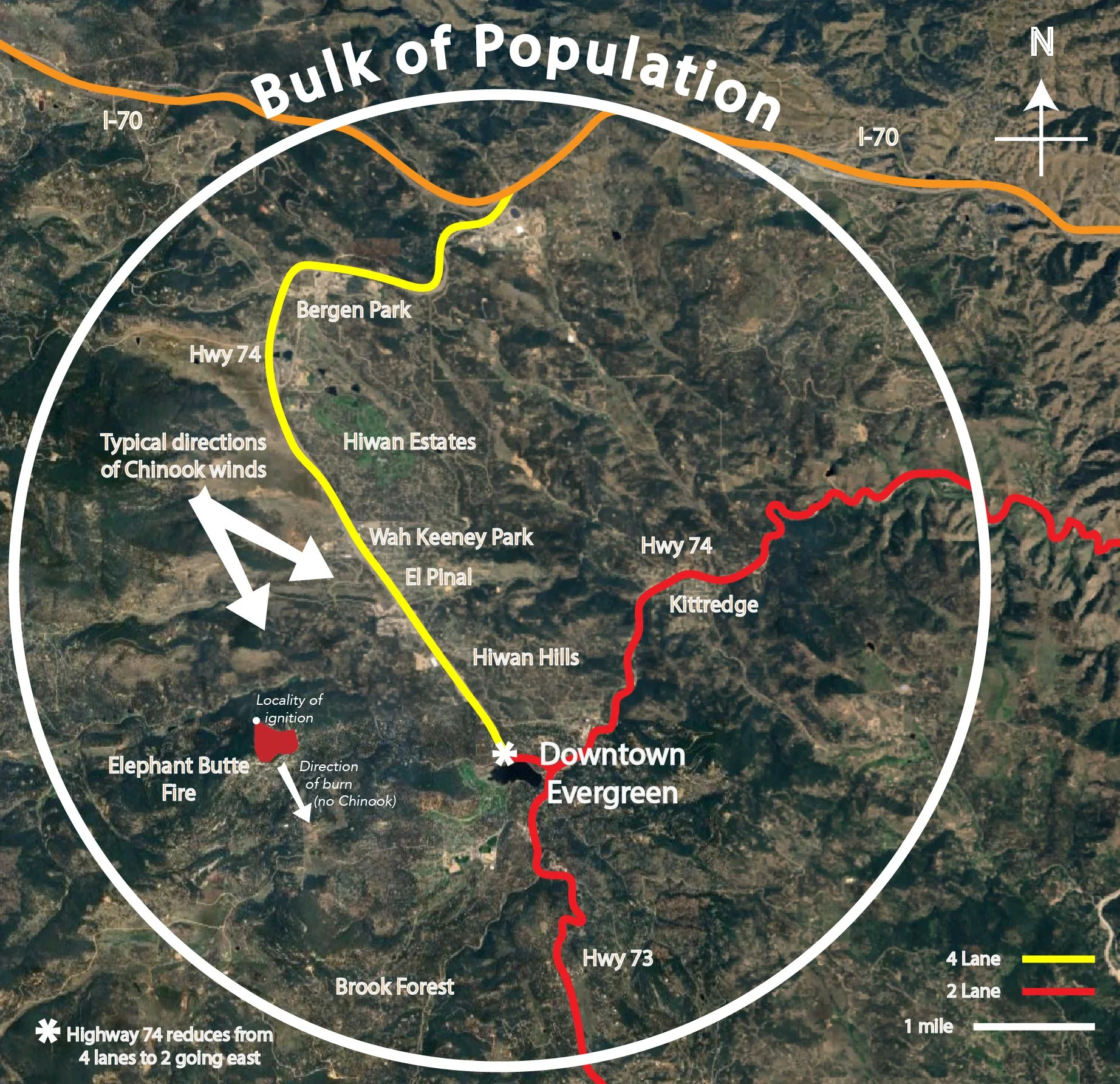

The 2018 California Camp Fire (Pt.3 Wildfire Series) - due to its massive size, speed, and cost in homes and lives - brought forward a somewhat unique problem mountain-terrain communities face; truncated and bottle-necked evacuation routes. For instance, HWY 74 is 4 lanes from I-70 almost to Evergreen Lake, then reduced to 2 lanes. Coming off any direction stemming out east or west is also confined to 2 lanes (HWY 73 to Conifer, 74 to Morrison, and Upper Bear Creek). If traffic backed up north along 74 from the lake, people might be inclined to try Stagecoach Road going east, only to run into a gate securing private property and a winding narrow dirt road.

Other elements in common with mountain communities: relatively high number of older residents/retirees, unreliable cell service in some parts, land-line communication can be severed, and the potential speed of a fire due to fuel abundance and unpredictable winds. There are also fewer evacuation routes than typical suburbs, and forests line and surround many of those.

There are a few paths of pre-arranged egress available over private land, as emergency access has precedents. JCSO can turn to these for alternate/additional evacuation routes if necessary.

Evergreen Fire/Rescue (EFR) Chief Weege explained that, as with the Elephant Butte fire, JCSO and EFR actively consult throughout evacuations to determine the best directions to route vehicles, JCSO then executes the plan. To add a fine point to the challenge, he recommended that if residents see a large column of smoke from their homes, instead of waiting for an alert they should take it as a sign to leave.

A possible general direction of a local fire if winds were high (as happens about 15 to 25 days a year with Chinooks - “Chinooks are occasional warm, dry föhn winds blowing down the eastern sides of interior mountain ranges”) is to SSE (south-southeast).

Although no Chinook wind was present, this direction was the case with the Elephant Butte fire, essentially following the Evergreen topography downhill. Chief Weege agreed that the Chinooks often travel down valley towards the lake, similar to how the winds drove the Camp Fire (regional terrain channeling downhill). So even though most of the year winds are too unpredictable to assume direction, late fall to early spring is typically the Front Range’s driest season and overlaps with the highest winds.

So to speculate that if a large fire broke out northwest of the lake, up to 10,000 people could be forced to evacuate southeast. To compound the problem, residents may be aware of how easily I-70, a 3-lane freeway each direction, can back up due to a broken-down truck, an accident, or slow vehicles. Steep and winding roads do not make for quick escapes, as might be attested by those trying to flee the Camp Fire.

Chief Weege also explained that the option of utilizing all lanes (contra-flow lane reversal) for evacuating vehicles would inhibit movement of equipment and personal, as is necessary in rapidly changing conditions. He did not say the option is ruled out, though.

Please continue with Pt.2 in the Wildfire Series – The Camp Fire

All photos/graphics TEO ©